Jonathan Berger - Miracles and Mud

I first encountered the St. Lawrence String Quartet during their 2009-10 artist residency at Arizona State University. Over the course of their visit, my peers and I frequently shared leery glances over the hemorrhaging stagemanship of first violist Geoff Nuttall, who tended to overshadow his relatively sedate colleagues. A decade earlier, classical music critic Alex Ross wrote: "When [Nuttall] plays, he has a habit of kicking one leg back and half getting out of his chair. His hair tends to change length and color; in El Paso, it was cropped short, with blond highlights. 'He looks like some dude from the beach,' a man at the back of the room whispered." Indeed, in 2010, his hair was longer, thoroughly brown, and more unkempt, and it shuddered sympathetically with every reeling gesture. The quartet's final concert of the residency became somewhat of a local legend, nostalgically recalled to this day as the bearing by which all subsequent concert experiences are judged. Although, regrettably, I was unable to locate the exact program notes for the concert, I suppose in some ways the continuing mystery only enhances the already mythologized event. I remember it was a concert of contemporary music, featuring R. Murray Schafer's rambunctious Third Quartet and a gorgeous, evocative piece for quartet entitled Doubles, by Jonathan Berger. That evening, the small concert hall was packed full. Some stood at the back; others ignored fire safety guidelines, crouching together along the stairs leading down to the hall's continental seating. The atmosphere was warm and heavy with respired air. As the lights dimmed, the A/C clicked off, and silence swept over the crowd. The musicians emerged single file from the back of the hall, accompanied by the familiar white noise of applause, took their seats and got to work. Afterwards, a friend and I walked home together in a moody silence, seduced into a sort of self-conscious catatonia, unable to express the trembling, nervous energy that coursed through our spirit.

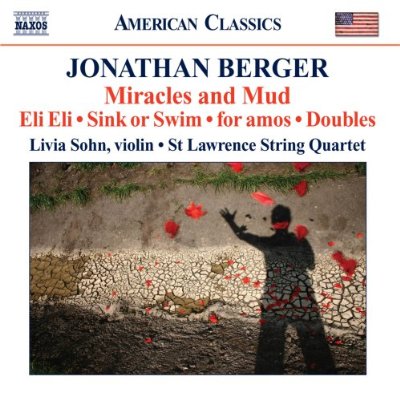

Miracles and Mud, an album of Jonathan Berger's chamber works, was released three years prior, in Summer 2007, as part of the American Classics Series on the Naxos label. The album opens with Eli Eli (a recording is available through Berger's website), a haunting, neoromantic tribute to the slain Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl. Adapted from David Zahavi's famous setting of a Hebrew poem by Hannah Senesh, it is not just a beautiful musical statement but a spiritual one. Rich, organ-like chords form the pulse of a funeral march, before giving way to a contrapuntal lament reminiscent of Grieg's Elegiac Melodies. Outbursts of despair are cut short by gasps for breath, as if to forcibly maintain the sanctity of religious ritual. In its dying breath, one can sense the unresolved doubt, and the piece concludes with the same throbbing dissonance with which it began, mournful, yet acquiescent to the unknowable workings of God.

Miracles and Mud, an album of Jonathan Berger's chamber works, was released three years prior, in Summer 2007, as part of the American Classics Series on the Naxos label. The album opens with Eli Eli (a recording is available through Berger's website), a haunting, neoromantic tribute to the slain Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl. Adapted from David Zahavi's famous setting of a Hebrew poem by Hannah Senesh, it is not just a beautiful musical statement but a spiritual one. Rich, organ-like chords form the pulse of a funeral march, before giving way to a contrapuntal lament reminiscent of Grieg's Elegiac Melodies. Outbursts of despair are cut short by gasps for breath, as if to forcibly maintain the sanctity of religious ritual. In its dying breath, one can sense the unresolved doubt, and the piece concludes with the same throbbing dissonance with which it began, mournful, yet acquiescent to the unknowable workings of God.

There is a ship and she sails the seas.

She's loaded down as deep can be,

But not so deep as the love I'm in

I know not if I sink or swim.

These lines, excerpted from a traditional Scottish-American folk song, form the basis of Sink or Swim, a set of variations for solo violin. Livia Sohn, Berger's Stanford colleague and the piece's dedicatee, shows impressive commitment to detail, living true to her bio's accolades: "every note rings true with pinpoint accuracy." The Molto Cantabile unfolds in ABA form. An understated introduction transforms into a raucous cadenza as animated figures begin to emerge, rising and doubling over one another as if in a panic, before subsiding into a breathless restatement of the opening material. Sink or Swim's inner two movements are akin in their caprice. Listening to the Risoluto, I am reminded of the Capriccio from Ligeti's Cello Sonata, which opens similarly with a noisy statement of the primary motivic material. Like Ligeti, Berger is careful not to venture too far from this rising interval motif, which unites the movement's schizophrenic episodes. It is not until the final movement that the piece's folksong theme is clearly stated, whistled lontano (as if from a distance) and with simple elegance. Sohn's earnest playing gives the movement the intimacy of a mother humming a bedside melody to her sleepless child.

In the SLSQ's recent performance-interview on NPR's Saint Paul Sunday, cellist Chris Costanza described Miracles and Mud as "an explosive, wonderful, ten minute piece, based on the conflict between the Israelis and Palestinians." In the album notes, Berger reveals that "the title is a pun on two types of coffee, one the European instant coffee (called 'nes' or 'miracle' in Hebrew) and the other, Arabic coffee called 'botz' (mud). Upon entering any household in Israel or Palestine the guest is often greeted with the question 'Nes o botz' (literally 'miracle or mud')." It was the first work commissioned of Berger by St. Lawrence, and it's a smorgasbord of experimental effects and textures. Unlike his later works for quartet, M&M is definitively modern, drawing from the bold and brash tradition of early twentieth-century composers like Bartók and Ives. Folk songs float over turbulent, polyrhythmic underpinnings; sprightly ponticello figures are interrupted by unison declamati; shrill exclamations give way to chilling silence. I feel like I'm getting jerked around in all directions, anxiously attempting to brace myself for the next abrupt change, and moments of repose serve only to emphasize the piece's overarching drama. Miracles and Mud paints a picture of two warring peoples, represented by two disjunct folk songs, and while it's certainly not dinner music, it carries with it a powerful message.

In the SLSQ's recent performance-interview on NPR's Saint Paul Sunday, cellist Chris Costanza described Miracles and Mud as "an explosive, wonderful, ten minute piece, based on the conflict between the Israelis and Palestinians." In the album notes, Berger reveals that "the title is a pun on two types of coffee, one the European instant coffee (called 'nes' or 'miracle' in Hebrew) and the other, Arabic coffee called 'botz' (mud). Upon entering any household in Israel or Palestine the guest is often greeted with the question 'Nes o botz' (literally 'miracle or mud')." It was the first work commissioned of Berger by St. Lawrence, and it's a smorgasbord of experimental effects and textures. Unlike his later works for quartet, M&M is definitively modern, drawing from the bold and brash tradition of early twentieth-century composers like Bartók and Ives. Folk songs float over turbulent, polyrhythmic underpinnings; sprightly ponticello figures are interrupted by unison declamati; shrill exclamations give way to chilling silence. I feel like I'm getting jerked around in all directions, anxiously attempting to brace myself for the next abrupt change, and moments of repose serve only to emphasize the piece's overarching drama. Miracles and Mud paints a picture of two warring peoples, represented by two disjunct folk songs, and while it's certainly not dinner music, it carries with it a powerful message.

In contrast to Miracles and the cantankerous erraticism of For Amos, the medieval drone intro of Doubles has me down on my hands and knees kissing the tonal dirt. Costanza emphasizes the musical double-life of Berger, a Stanford professor and researcher in the highly experimental field of acoustics and computer-driven music, who nonetheless composes with "a very traditional quartet voice." A pastoral melody drifts effortlessly over Elysium until soft, dissonant tones emerge like a ringing in one's ear, or the highbrow Nuttall-ism: "it's like outer-space time." Like glitches in the Matrix, these tones reveal a world beyond the fantasy, emblazoned with the oxymoronic beauty of misery, machinery, and mortality. Berger's use of atonality in Doubles is palatable and compelling, balanced by lyrical passages and certain pseudo-tonal elements. The polyphonic fifth movement is tragic, almost Pärtian, warm-blooded, and heart wrenching. Subito Brutale propels the quartet into a swashbuckling finale whose short-short-long rhythmic motif is plundered from the end of the fourth movement. Despite this, the consistent tonality and forward momentum here is pretty much uncharacteristic of the rest of the piece, more calling to mind the saucy last movement of Brahms' G Minor Piano Quartet than any 20th-century personalities.

Berger's music stands as a testament to the vehement cosmopolitanism of today's music. The otherworldly textures in the second movement of Doubles left me giddy and goosebumped, yet other times, like during the relentless, pot-banging clatter of For Amos, I caught myself reaching for the volume control. Seven of the album's 19 tracks are entitled as some variant of ballyhoo—frenetic, agressivo, furioso, brutale—and that's not counting the 13-minute panic attack that is Miracles and Mud. Like all music, especially contemporary art music, a lot of the performance magic doesn't make the leap from stage to recording. That said, if the St. Lawrence String Quartet ever gives a recital in your town, do yourself a favor and attend. And if there's a piece by Berger on the program, hold on to your socks. It'll be an evening you'll never forget.