Svelton - Oblivion

You open your eyes to an industrial dystopia. Churning clouds of purple-gray obscure all but your immediate surroundings. Phosphorescence refracts through the mist, illuminating monolithic structures rising from the ground; ruins, perhaps, of a civilization long extinct. Your mind is blank. With no idea who you are or where you came from, you take your first steps into the unknown.

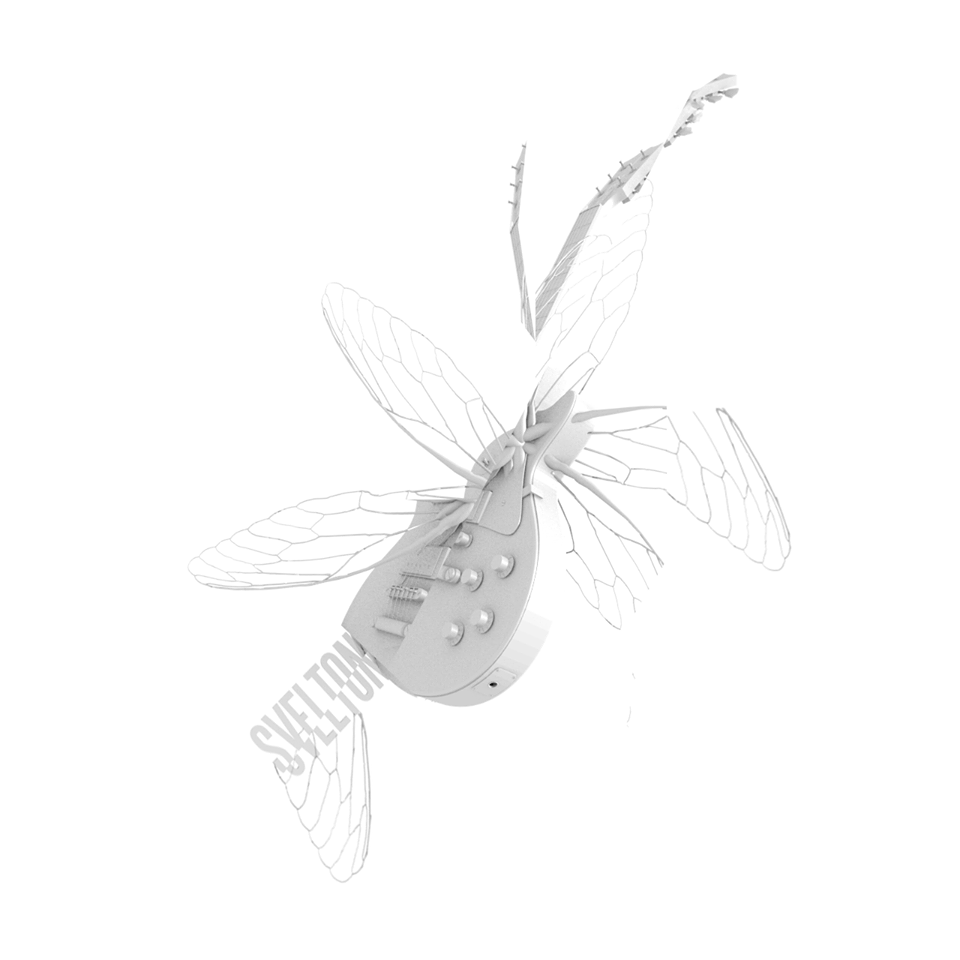

That's the world as seen by Evan Marcell Snyder, the thrice-named brains behind the evocative, electro-industrial project Svelton. For Snyder, music and the visual world are inextricably intertwined. When I prompted him to describe his music, he immediately asked for a pen and paper, sketching abstract representations of computer networks while describing the similarly organic nature of musical compositions, which, through their complexity, come to have a life of their own.

Artwork © Ryan Samples

Artwork © Ryan Samples

"Or maybe I just want to think that," he clarified, "because it's this presence that I feel, that I want to be organic, that seems organic, and that I want to be this other presence. And, in the end, we don't want to feel so alone, so sometimes we make up these presences out of things that really only look like presences."

Questioning the nature of one's own perception is a theme throughout Svelton's newest album, Oblivion. Combining grungy electronic synths, phased-out vocals, and complex Brazilian-inspired drum tracks with the industrial quality of Nine Inch Nails, Svelton is a tasty creole of mixed influence. From the get-go, A Single Word pairs stubbornly off-kilter drums and a limping harmonic cycle. Making concrete sense of it can be an overwhelming exercise, like losing oneself in a strange dream world, such that the familiar chop of helicopter blades midway through the track is a snap back into consciousness. Vocals emerge at this crossroads...

I could say anything now

And I would not be heard

But I cannot relate a single word

...practically suffocated by a tumultuous atmosphere of effects, culminating in a breathless, crumbling instrumental finale. On the other hand, If You Could Exist2 has a pleasant respiratory aspect to it, with it's grumbling midi bass and soft harmonies. A strange thing happens at 3:20 when the rhythmic/harmonic momentum unexpectedly dissipates; it's as if something catches the eye, leaving one temporarily afloat in a nuanced swath of sound, listening intently for disturbances.

Whether he's performing, composing, or out photographing dead bugs on the sidewalk, Snyder is constantly engaged with his art. He does all of the artwork for Svelton, which comprises two independently released albums so far, and maintains the band's intriguing website. Vigorously self-taught, Snyder composes with a sort of veiled poignancy, and his music therefore lends itself to critical listening; nestled among the glitchy, mechanized clamor, are glimpses into an ongoing storyline of personal deconstruction in a foreign world. The schizophrenic We Have to Leave unites diametrically opposed musical sections; following a rousing call-to-arms opening, it stitches together a buggy 7/4 groove and periods of stark repose that reveal a mournful euphony in the upper voices. Nearness of You slowly spins up a symphonic whirlwind which gives way to expose a latent aleatoric piano melody, like the memory of a loved one piercing through the fuzz of everyday life. A pentatonic organ melody from earlier in the track reappears four tracks later, foregrounded but laboring to develop under the pressurized atmosphere of Oblivion. Then there's Protector's all-caps adrenal energy, obsessively single-minded and physically stirring. Like the trained visual artist he is, Snyder takes a palette of pop sounds and manipulates them to uniquely expressive ends.

Perhaps at times, Snyder's tendency to challenge pop music precepts expects a lot from listeners. Probably the most pop-ish track on Oblivion is Past the Way Out, where Snyder's grimacing vocals and the nautical soundscape have a tinge of Toro Y Moi to them, albeit more cold-sweated. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Tear (note the double-entendre) is an organic discourse scrawled on an eclectic, multimedia-style canvas. The perplexing thing about Tear is that it doesn't particularly use rhythm and harmony to generate tension and release and compositional unity, but rather long-form motivic development, à la contemporary classical music.

Snyder hangs from the rafters at a show in Cleveland.

Snyder hangs from the rafters at a show in Cleveland.

In spite of Snyder's nephalism, Svelton's darkness and musical complexity is best appreciated by means of a good pair of headphones and a glass of red wine. Like a Zinfandel, it's spicy, idiosyncratic, and full of personality; though I would love to see his take on a sweeter, more delicate Pinot Noir, if you catch my drift. With the completion of Oblivion comes a new chapter in the Svelton Saga: Snyder indicated that he would like to expand upon some of the more narrative elements, and his recent flirtation with After Effects could signal a desire to transform Svelton into a full-on Gesamtkunstwerk. Yet, forecasting the output of this ebullient and industrious Clevelander might prove a fruitless endeavor. As he said, ever so matter-of-factly: "it's nice to be left hanging sometimes."